Hello

We Are Team Speak Up

Our Mission is to Democratize Audio Production with Machine Learning

check out our project Live Demo and Repository

The Team

| Matt Linder |  |

|

| Rana Ahmad |  |

|

| Wilson Ye |  |

|

Background and Significance of Project

Audio is invisible. On its face, this might seem like the most obvious statement in the world - humans literally can’t see sound (unless they have synesthesia…). But what I mean is this: humans are visual-dominant creatures and because we can’t see audio, it’s easy to miss its importance - and its impact. This impact is felt in so many areas of media, but let’s scope it just to spoken audio. Research has shown that people are more likely to trust information that comes to them as higher quality spoken audio.

Whether they’re aware of it or not, people are more likely to consume content that sounds better, but the problem is - it’s difficult and time-consuming to make spoken audio sound professional.

Instagram, Snapchat, Tiktok, and YouTube have revolutionized photo and video content creation - giving consumers access to filters, effects, and editing techniques that used to be the realm of professionals. The same revolution has not yet come for spoken audio.

There are plenty of DAW plugins and other products that can produce amazing results, but given the fact that maybe only 5-10% of my audience understood that ‘DAW’ stands for ‘Digital Audio Workstation’, it’s clear that these products are out of the realm of your typical consumer. The vast majority of content that has professional-sounding audio is either recorded by professionals or by amateurs who have spent large amounts of time and money learning to record and engineer audio.

This is where SpeakUpAI comes in. We want every aspiring podcaster, YouTuber, MOOCs teacher, and every other creator of spoken audio content to be able to produce professional-sounding audio. With SpeakUpAI’s state of the art machine learning technology, users can simply record spoken audio on their phone or tablet, upload it to our site, and our ML model will return an ‘enhanced’ version - denoised, dereverberated, normalized, EQ’d, etc, etc. - for them to download and use in whatever application they choose.

SpeakUpAI wants everyone to sound professional. We’re hear to democratize audio.

Explanation of Data sets

We’ve intentionally sourced the same three datasets that were used in the creation of HiFi-GAN, the academic paper upon which we’ve based our research.

Speech - DAPS

As the creators of the DAPS dataset describe it:

A dataset of professional production quality speech and corresponding aligned speech recorded on common consumer devices. […] This dataset is a collection of aligned versions of professionally produced studio speech recordings and recordings of the same speech on common consumer devices (tablet and smartphone) in real world environments. It consists of 20 speakers (10 female and 10 male) reading 5 excerpts each from public domain books[…]

(They even have a paper they wrote about it!)

This is a dataset that is more or less tailor-made for our application - supervised learning for speech denoising. We have high-quality studio recordings of many different speakers (10 male and 10 female) for training. The unaltered audio (in .wav format) of these recordings acts as our output/target (or y), and we perform pre-processing and convolution on that same audio with our Noise and Impulse Response datasets to create our input (or X).

Additionally, we have the same twenty speakers reading the same material on different consumer devices in different real-world environments for testing. This really is perfect for our application, since it allows us to test generalization on never-before-seen examples while still maintaining conceptual continuity for subjective testing. These test examples also very closely mirror our intended use-case for our model - processing audio recorded across different devices in many different environments.

If our model generalizes well to this test set, but performs significantly worse on other real-world examples, it will give us a much clearer idea of whether we’re overfitting on the 18 specific speakers in our training set. In turn, this will allow us to better tweak our data collection and pre-processing to make the model more robust.

Noise - ACE Challenge dataset

Our “Noise” dataset is a collection of audio recordings focusing on what would typically be called background or ambient noise - the hisses, hums, and other persistent sounds present in almost all non-professional audio recordings. Because our audio targets are (intentionally) devoid of such noise, we use this dataset to add it back in and create our input data.

In this case, we’ve sourced the ACE Challenge dataset.

Impulse Response (Room sound/reverb) - REVERB Challenge dataset

Another important aspect of audio recordings - and one that’s particularly noticeable in professional recordings in particular - is the impulse response or ‘room sound’ of the space in which the recording is made. This is often referred to in the audio industry as ‘reverb’ (short for reverberation), and most professional voice-over, podcast, and other spoken media go through great lengths to minimize the audience’s perception of the room in which the media was recorded (this can be referred to as making a recording ‘dry’).

Because our output audio from the DAPS set is already very dry, we create our inputs by convolving the output with a variety of impulse responses taken from the REVERB Challenge dataset.

Explanation of Processes (Methods)

HiFi-GAN

As the authors explain:

Real-world audio recordings are often degraded by factors such as noise, reverberation, and equalization distortion. This paper introduces HiFi-GAN, a deep learning method to transform recorded speech to sound as though it had been recorded in a studio. We use an end-to-end feed-forward WaveNet architecture, trained with multi-scale adversarial discriminators in both the time domain and the time-frequency domain. It relies on the deep feature matching losses of the discriminators to improve the perceptual quality of enhanced speech. The proposed model generalizes well to new speakers, new speech content, and new environments. It significantly outperforms state-of-the-art baseline methods in both objective and subjective experiments.

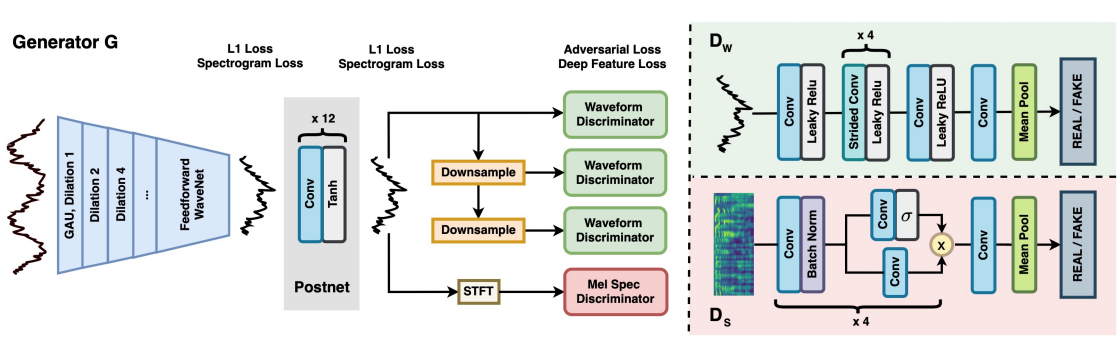

Here, generator G includes a feed-forward WaveNet for speech enhancement, followed by a convolutional Postnet for cleanup. Discriminators evaluate the resulting waveform (Dw, at multiple resolutions) and mel-spectrogram (Ds).

On a practical level, we’re using a PyTorch implementation of the HiFi-GAN model, forked from the awesome folks at w-transposed-x. As with any deep learning projects, our initial efforts went towards getting the model up and running (aka lots of troubleshooting), test runs, and hyperparameter tweaks based on performance.

We did initial testing on Google Colab, which is great for testing since it’s an inexpensive platform. The disadvantage, however, is that users are limited to VMs with a single GPU.

So, once we got hyperparameters and performance to a functional level, we moved to Amazon EC2 (+ S3 for storage). EC2 instances have the advantage of being scalable - since our PyTorch implementation was built for distributed training on up to 4 GPUs, we spun up a 4GPU instance and started testing.

Currently, we’re dealing with performance scaling issues between our single GPU training on Colab and the four GPU EC2.

Pipeline

Currently, work on HiFi-GAN is limited to audio recorded at 16khz sample rate. True high-fidelity audio is recorded at sample rates of 44.1khz or above. To this end, we’ve also implemented an Audio Super Resolution U-Net model, with the intention of training it on 44.1k audio downsampled to 16k.

Once we have this model trained, we can use it after HiFi-GAN in a pipeline to take raw speech audio, enhance/denoise it, and then upsample it to the desired high-fidelity sample rate.

Currently, we have our super resolution U-Net properly implemented in TensorFlow 2.x (it was originally implemented in 1.x, and the porting process was time-consuming), though further training work will wait as we optimize HiFi-GAN.

Explanation of Outcomes (current results)

Example 1 - “Familiar voice, new environment”

We take a small clip of audio from our DAPS dataset, recorded on a common consumer device (iPad), and we run it through our HiFi-GAN archicture.

Before HiFi-GAN

/project-update-media/f5_script5.wav

After

Version 1 (~2% of original training)

/project-update-media/f5_script5_v1.wav

Version 2 (~10% of original training)

/project-update-media/f5_script5_denoised.wav

Subjective Results

As you can hear, almost 100% of the background noise (often described as ‘hum’ or - in this case - ‘hiss’) has been removed, even in Version 1. In its place, however, you can hear very noticeable ‘artifacting’ in the spoken voice.

In Version 2, however, the voice starts to sound quite a bit more natural. And remember, this is with only about 10% of the original training schema, on a fraction of the original dataset, without having implemented all of the original data augmentation.

Example 2 - “New Voice, new environment”

Before HiFi-GAN

/project-update-media/f10_script5.wav

After

Version 1 (~2% of original training)

/project-update-media/f10_script5v1.wav

Version 2 (~10% of original training)

/project-update-media/f10_script5v2.wav

Subjective Results

The results here are extremely similar, but what’s significant is the fact that this voice - Female Voice 10 - was not used at all in training the model. It’s a completely new, unfamiliar voice, and you can hear that the model generalizes to it quite well. We find these results EXTREMELY promising.

Objective Results (metrics and analysis)

We’re evaluating the quality of our model’s results using two main metrics:

- PESQ: “a worldwide applied industry standard for objective voice quality testing used by phone manufacturers, network equipment vendors and telecom operators”

and

- STOI: “based on a correlation coefficient between the temporal envelopes of the time-aligned reference and processed speech signal in short-time overlapped segments”

Goals:

Based on the results table of the HiFi-GAN paper (PESQ numbers first, STOI second):

We’ve set our PESQ goal to be 1.5, just above the level of Wave-U-Net, a deep learning solution.

We’ve observed the STOI benchmark to be significantly more difficult to achieve, so we’ve set our goal to be 0.70, or about 82% of the deep learning baseline set by Deep FL.

We’ve set slightly reduced baselines here, due to the scope restraints of the current work. We’ll only have the chance to train our model for a tiny fraction of the original HiFi-GAN training schema, which was:

- 500,000 steps training the base Wavenet

- 500,000 steps training the Wavenet + Postnet

- 50,000 steps training all of the GAN elements (including the Wavenet, Postnet, and all four discriminators)

Version 1 and 2 results:

Version 1 of the model had a training schema of:

- 12,000 steps on Wavenet (2.4% of original)

- 12,000 steps on Wavenet + Postnet (2.4% of original)

- 1,200 steps on all GAN elements (2.4% of original)

Version 2 of the model had a training schema of:

- 50,000 steps on Wavenet (10% of original)

- 50,000 steps on Wavenet + Postnet (10% of original)

- 5000 steps on all GAN elements (10% of original)

We’ll be publishing Jupyter Notebooks with full analysis of the various Version results once we finish version 3, but for now, we’ll break down the results by environment and speaker, since the impact of those on model performance is quite clear.

Evaluation Set:

We created the same evaluation set as the one used in the HiFi-GAN paper. Our training and test sets were made from the DAPS dataset, part of which is professional studio recordings of five scripts, read by twenty different speakers (ten male, ten female), though we held out one speaker of each gender for testing and one whole script for evaluation.

The DAPS dataset also includes recordings of the same five scripts by the same twenty speakers, but this time recorded on different consumer devices (iPhones and iPads) in several different environments (Balcony, Bedroom, Conference rooms, Living room, and Office).

Our evaluation set is made up of the holdout script (never seen in testing) recorded by all speakers in all of these different environments. We ran inference on all 240 such clips (20 speakers x 12 various combinations of devices and rooms) and ran our PESQ and STOI metrics for evaluation.

Environment

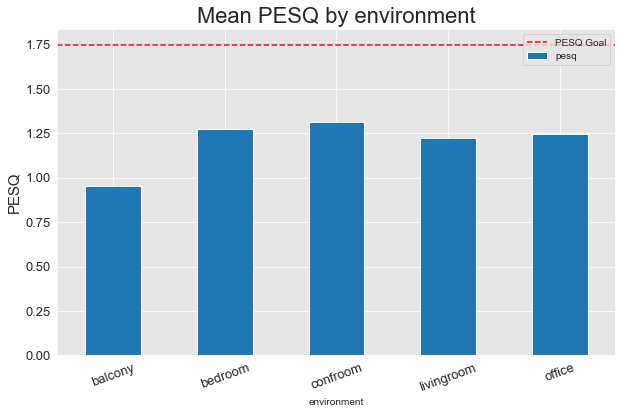

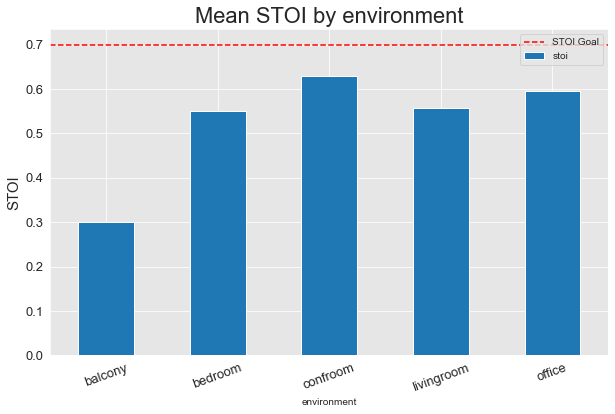

Version 1

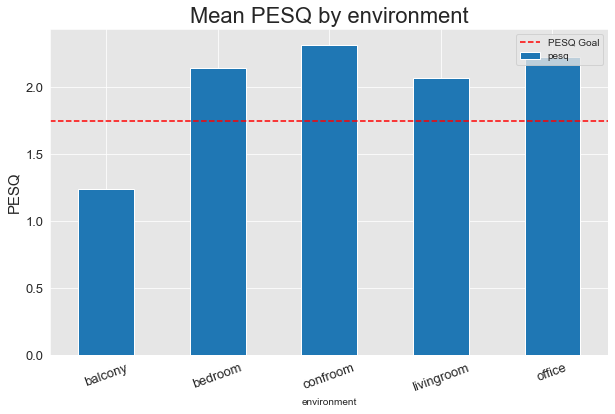

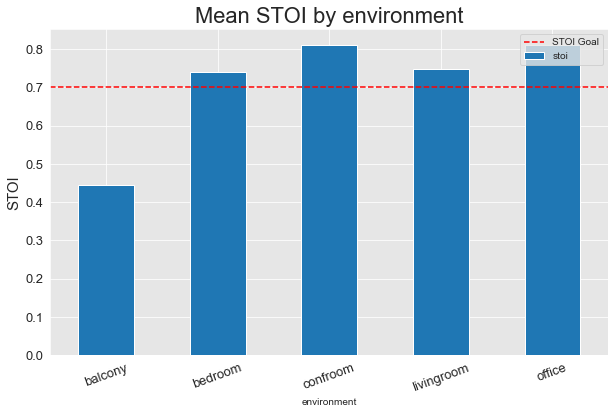

Version 2

Clearly, the additional training steps between versions 1 and 2 made a ton of difference, and in version 2, we were able to exceed our PESQ and STOI goals on every environment except for the Balcony. The Balcony is by far the toughest environment in the dataset - being outdoors, it has significantly more background noise. Once Version 3 is training, if we’re still not meeting our goals on the Balcony, we’ll refactor our noise data augmentation to better match the amount and type of noise present in this outdoor environment.

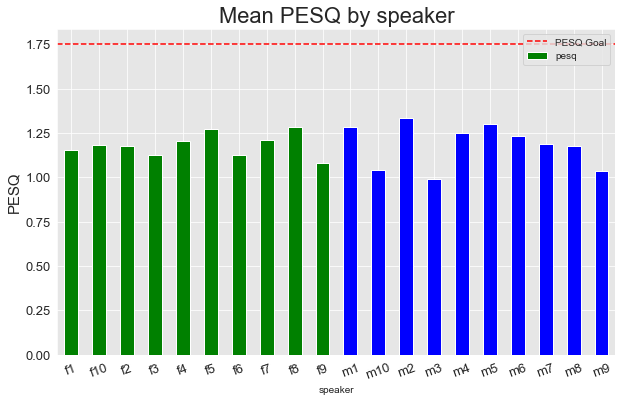

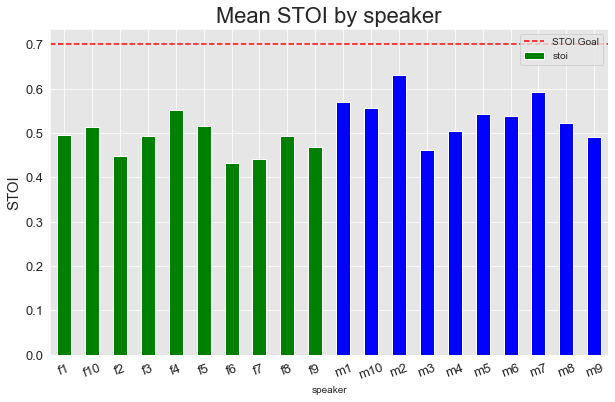

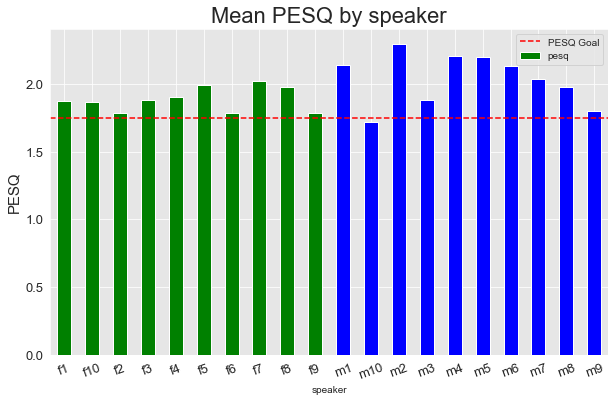

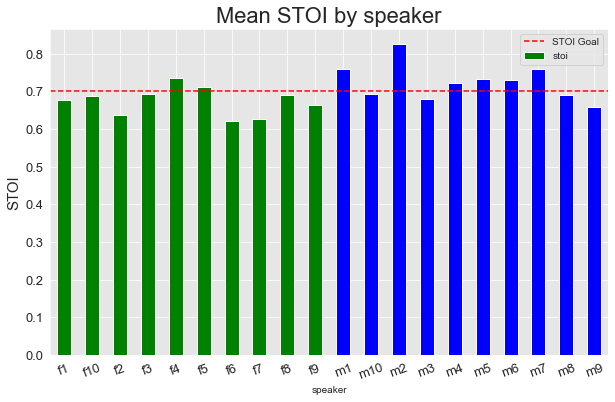

Speaker

Version 1

Version 2

Similar to the metrics grouped by environment, we can see ranges of performance in PESQ and STOI across the different speakers. Overall, the model tended to perform better on the male voices, though there was a wider range.

The additional training for version 2 also had a similar impact, bringing the majority of PESQ scores above our goal threshold.

Overall, though, version 2 is already hitting our overall PESQ and STOI goals with mean PESQ of 2.042631 and STOI of 0.727752 across all evaluation examples.

System Design and Ethical Considerations

Overall System Design

You can read in MUCH greater detail about the system design of HiFi-GAN in the original paper, but in a nutshell:

The model is a GAN architecture using a Wavenet architecture (plus an optional simple convolution-based “Postnet”) as the generator network with four(!) discriminator networks. Three of these are waveform-based - one utilizing with audio at original sample rate, and the other two downsampled by factors of 2. The last discriminator is Mel Spectrogram-based, and the adversarial loss is added to a relatively novel concept called “Deep Feature Loss”, about which you can read in the original paper.

We chose this architecture because:

- The results shown on the DAPS dataset were the most impressive we found in our survey of ML-based speech-enhancement.

- Using heterogenous sources - waveform and Mel Spectrogram - in the adversarial architecture of a GAN seems extremely promising. Most previous audio-based GANS are 100% spectrogram based, and as such, tend to have serious phase-related issues.

HiFi-GAN System Design

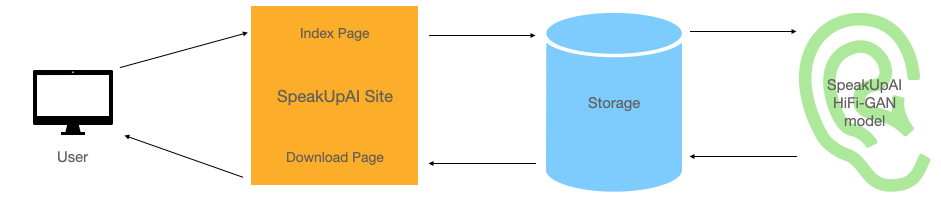

This is subject to change as we develop and iterate our process and deployment, but for the moment, system design looks like:

This is subject to change as we develop and iterate our process and deployment, but for the moment, system design looks like:

- A user navigates to the SpeakUpAI website, where they land at the index page. There, they are prompted to upload an audio file for enhancement.

- Once they choose a file and click

Upload, that file is sent to SpeakUpAI’s storage (an S3 bucket, for the moment), and then passed to our HiFi-GAN model for inference. - When inference is complete, it spits out an audio file (

.wav), which is then moved to our storage, and the user is prompted to download the enhanced file. - Once the user downloads their enhanced file, the original and enhanced versions are erased from our storage.

Ethical Considerations

Since we’re designing a fully opt-in system that doesn’t request any sensitive information, our ethical considerations fall into two main categories:

- Data Privacy

- Bias towards/against certain types of speaking voices/languages

Data Privacy is obviously important, since users’ audio: a.) is their own creative work and potentially subject to copyright or other intellectual property laws, and b.) could potentially contain sensitive information.

To that end, it’s our mission to make sure that our network and storage systems are as secure as possible, and that users’ content is completely erased from our system as soon as they’ve downloaded their enhanced audio.

Bias is always a concern in ML systems, and it takes many forms. But, in this case - we’re concerned with bias towards or against certain voices, accents, or languages. At the moment, our scope only gives us time to focus on English speakers, so extending the training to other languages will come later, but part of our current model evaluation will relate to how it is able to generalize to speakers with voices and accents different from those in the training and validation sets.

Future work

- Use sonic analysis of noise and IR in underperforming environments to sculpt noise/IR augmentation for further training

- Implementation of Bryan/HiFi-GAN Impulse Response augmentation

- Longer training of Generator (wavenet and wavenet-postnet) models

- Using Audio Super-Resolution model to upscale results from 16k to 44.1k (and beyond!)

- Taking different audio/video formats as input - currently only

.wav - Optimizing inference performance (currently works at near-realtime on a single GPU)

- Implement Dask/Spark on deployment infrastructure to deal with large files

- Creation of more varied datasets (in terms of languages/accents/voice types) by scraping high quality audio sources (NPR, etc.)

- Implement sliding window technique

Related Work (Papers, github)

This is by no means comprehensive, but the following are some of the papers, repos, and products we researched while creating SpeakUpAI. Items marked with “***” are directly utilized in our research.

Automatic Mixing

Vocal DeNoising specific

Papers

- Audio Super-Resolution using Neural Nets ***

- Practical Deep Learning Audio Denoising

- Audio Super-Resolution using neural networks

- Speech Denoising by Accumulating Per-Frequency Modeling Fluctuations

- using Deep learning to reconstruct high-resolution audio

- Speech-enhancement (denoising)

- Conventional DSP Noise Reduction

Products

Audio and De-Noising GANs

- WAVEGAN ***

- HiFi-GAN ***

- Magenta GANSynth

- DN-Gan for Denoising and code